RUM, RHUM, RON (3)

In recent years, we have not seen such a significantly strong wave of interest in the alcoholic beverage market as in the case of rum.

Before rum reaches your glass, it undergoes a unique and meticulous production process. Beyond the quality of the raw materials, it is the various production methods, approaches, and specificities that are the crucial factors influencing the final outcome.

Harvest

Sugarcane harvesting is a veritable ritual in every country. The arduous work of harvesters is increasingly being replaced by combines. A large number of people are involved in the process, and perfectly timed transport of the cane from the fields to the sugar mills, or directly to the distilleries, is crucial. Time is of the essence, as the quality of the cane is subject to oxidation processes. Upon arrival at the factory, it is then weighed and its sugar content measured.

Recycling

At the factory, the sugarcane is fed into a hopper, which gradually moves it to the mill. In the mill, the raw material is crushed, and the flowing juice passes through a filter that collects impurities and foam into a collection vessel. To extract as much juice as possible, this cycle is repeated two to three times. The juice then flows through a system of pipes into large storage tanks. The waste remaining after pressing is an ideal fuel for electricity generation or ends up in the fields as fertilizer. Literally everything from the sugarcane is utilized. Rums made from molasses or fresh cane juice follow the same processing procedures. The main difference lies in the type of raw material used.

Fermentation

The next step in production is fermentation. For this purpose, carefully selected yeasts are used in most cases, but there are also producers who prefer more prolonged natural processes. The process itself lasts from a few hours for “light” rums, 10 to 15 days for agricultural (agricole) rums, up to long fermentation for “heavy” rums, which can take up to three weeks. At the end of fermentation, a so-called cane wine with a low alcohol content is formed. The temperature and humidity of the surrounding environment in which fermentation takes place also play an important role and must be within a certain range.

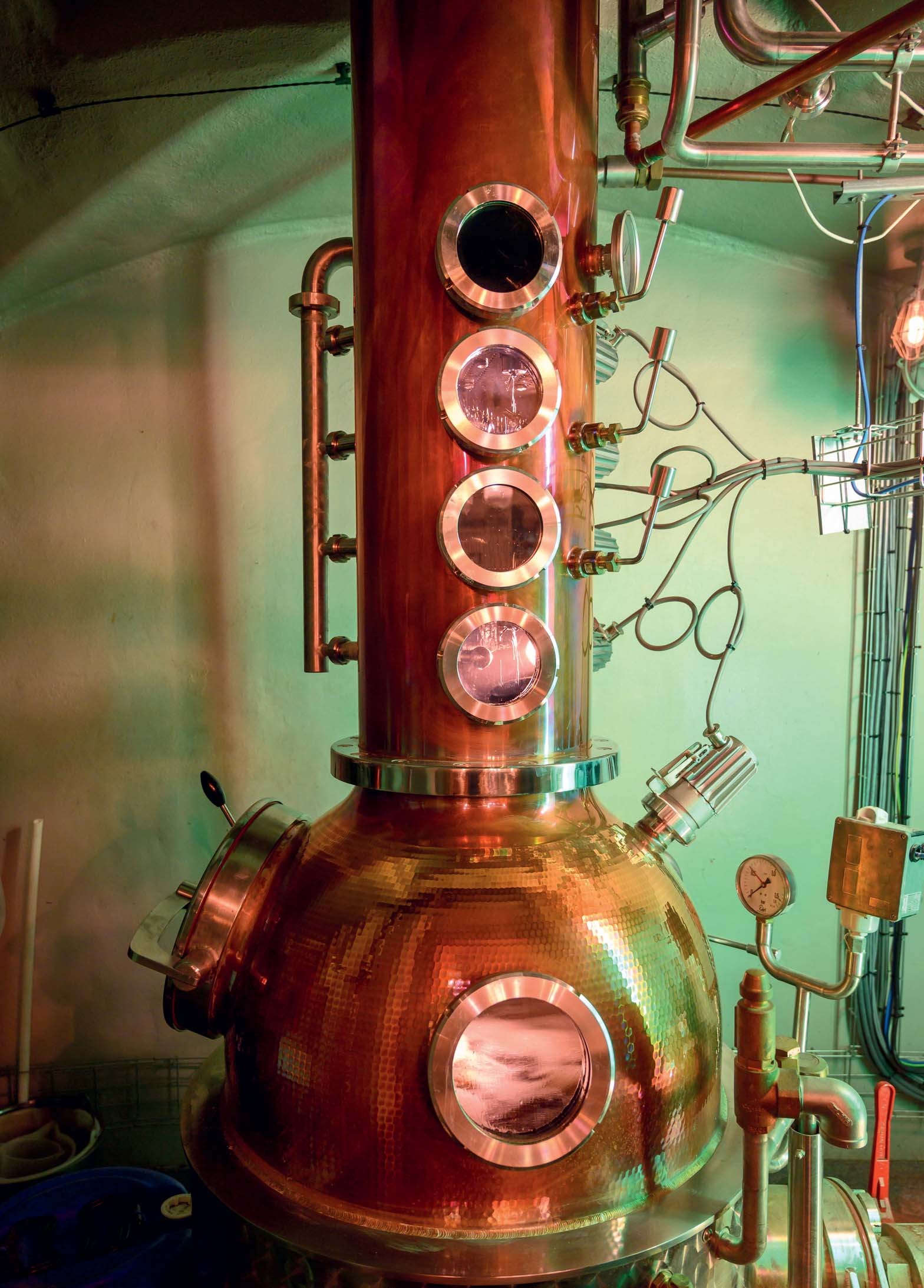

Distillation

Pot still distillation is an older method. In the first phase, approximately 25 to 30 percent alcohol is obtained, followed by a distillate with an alcohol content of 70 to 75% in the second phase. Rums distilled using the pot still method are generally heavier, with an oily texture and distinctly aromatic. The second, more modern method, is the column still. Up to 90% of rums are produced this way. Qualitatively, rums distilled in this manner are lighter, smoother, and less aromatic, with an alcohol content ranging from 70 to 95%. The taste, smoothness, and quality are also influenced by the number of distillation cycles. The result of distillation is a clear, colorless liquid, similar to an unaged spirit.

Angel's Share

Subsequently, the rum must rest. For this purpose, large open oak or stainless steel vats are used, in which the rum naturally rids itself of undesirable volatile substances. This stage lasts from several weeks to several months. Approximately 10% of the volume evaporates, which producers call the ‘Angel’s Share’. It is essential to monitor and stir the spirit throughout this period to allow the flavors and aromas to fully develop, and with the gradual addition of neutral water, the alcohol content is intentionally reduced to the desired level.

Flavoring

At the end of this process, white rum is bottled and is mostly preferred for mixed drinks. Exotic combinations are also very popular, where a macerate of tropical fruits, spices, vanilla, coffee, or caramel is added to white rum, creating interesting recipes. However, for white rums, there is also scope for longer maturation in oak barrels and subsequent filtration through activated charcoal to regain their original clear color. Alternatively, the rum may be stored for several weeks in oak barrels to acquire a fruitier and rounder taste.

Aging

The aging of rums is a chapter unto itself. After resting, white rum is filled into oak barrels, where it remains for several months to several long years. Barrels are specifically chosen to achieve a particular profile for the final product. It is in these barrels that the rum acquires its specific color, aroma, and taste. The most preferred barrels are those made from French and American oak. These are often barrels previously used for aging cognacs, brandies, bourbons, as well as fortified wines – port and sherry. Barrels are typically charred and sanded before use. The tannins contained in the oak wood influence the rum’s color and taste during aging. The barrels also take their toll. In tropical conditions, 7 to 10% of the rum evaporates from the barrels, while in temperate climates, it is approximately half.

Climatic Influence

In the tropics, aging occurs significantly faster, and rum ages three times faster than cognac or whisky. Thus, a four-year-old rum in tropical conditions can equal the quality of a 12-year-old whisky. A unique aging system is the Solera system. Barrels containing rums of various ages are stacked on top of each other in a pyramid shape, with the oldest rums at the bottom and the youngest at the top. They are intentionally blended, thereby accelerating the rum’s aging process. The labels of rums aged in this manner always state the age of the oldest rum used in the bottle.

Inconsistent Rules

For most rums, the number of years spent maturing in oak barrels is stated. However, no uniform rules have been established worldwide. The world of rum is diverse, full of flavors and aromas, with endless possibilities for discovery.